Following on from the culmination of the Curriculum and Assessment Review, Teaching Medieval Women is disappointed by the Review’s failure to acknowledge or tackle the critical under-representation of women in school History.

On 5 November 2025, the long-anticipated Curriculum and Assessment Review final report was published. One of the key aims of the Review, when it was launched in July 2024 and chaired by Professor Becky Francis CBE, was to deliver ‘a curriculum that reflects the issues and diversities of our society, ensuring all children and young people are represented’. Though the final report called on the UK government to ‘[s]upport the wider teaching of History’s inherent diversity’, the report made no reference to the limited representation of women in school History. In their official response to the report, the Department for Education (DfE) promised to support the teaching of the ‘innate diversity of British history, including British Black and Asian history’ amid its pledge to strengthen students’ ‘understanding of our nation’s history’. Where women fit into this picture remains unclear. That neither the report nor the government’s response mentioned the under-representation of women shows where both the panel and the government may have missed a crucial opportunity to tackle the current gender imbalance in school History.

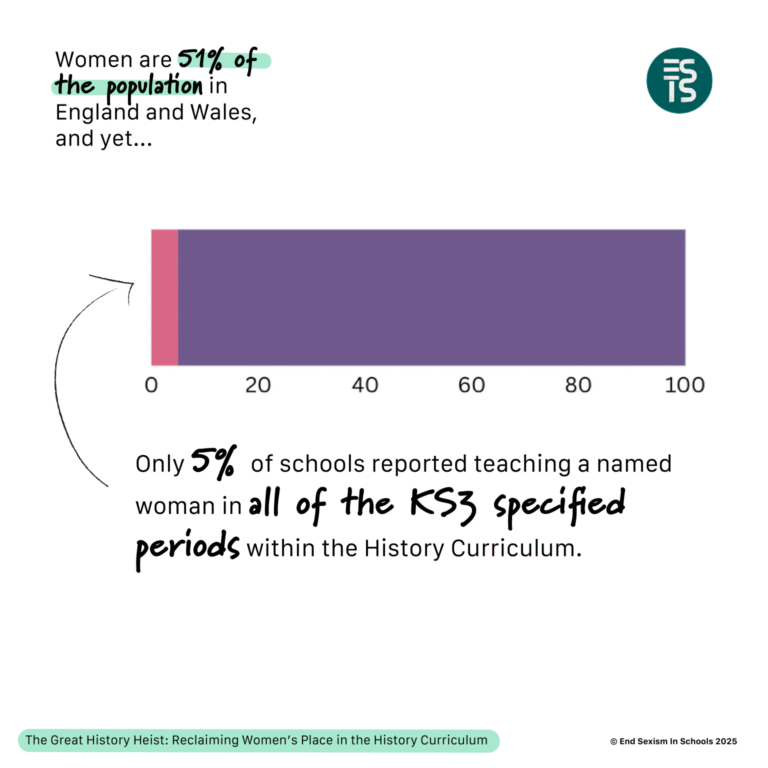

This failure comes despite growing research into the issue. TMW’s Natasha Hodgson co-authored a report with the End Sexism in Schools project which looked at the current Key Stage 3 History curriculum. This report found that 59% of History lessons given to 11–14 year olds featured no women at all with only 12% of lessons focusing on a historical woman. This coverage was largely limited to four ‘exceptional’ women, namely the Tudor queens, Mary I and Elizabeth I, and the suffragettes, Emily Davison and Emmeline Pankhurst.

This disproportionate representation of women carries on into Key Stages 4 and 5. In a survey of History textbooks, Laura Aitken-Burt identified where ‘67% of all A level and GCSE specifications currently studied have not even one named female character to study’. Overall only 6.8% of named persons in History textbooks were women. In a survey of History GCSE and A Level papers issued in 2023 by the three largest English exam boards, Natasha Hodgson and Catherine Gower found that students were directed to discuss women in their answers for 6% of questions, whereas they were directed to discuss men in 36.5% of questions. Across all 219 exam papers, women were only named in questions in 31 instances compared to 326 instances where historical men were named in questions. Representation of women overall was limited again to a few exceptional figures, with the most frequently referenced woman being Elizabeth I who appeared in 9 questions.

In November 2024 TMW submitted evidence to the Review, calling for greater reform of the existing History curriculum to ensure a more balanced and accurate coverage of the role of women in pre-modern History. One recommendation raised was for the inclusion of a broad range of historical women from global contexts to existing module specifications, course materials and exam content. Ensuring better representation of women in the History curriculum, equivalent to the representation of men, is important to tackle current problems, such as the reported rise of misogyny in schools, one that appears to be fuelled by populist misinterpretations of the past.

With the DfE promising to reform current specifications to ensure greater clarity, now would be a good time to address the inherent gender imbalance in school History as well as to meet the Review’s original objective of ensuring that all children and young people are represented in the curriculum. Until historical women are represented in History lessons to the same degree as historical men, the curriculum remains in dire need of reform.